Reclaiming Our History: Malala Yousafzai, and Men’s Place in Women’s Liberation

Meet Malala Yousafzai, a Pakistani activist, film producer, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

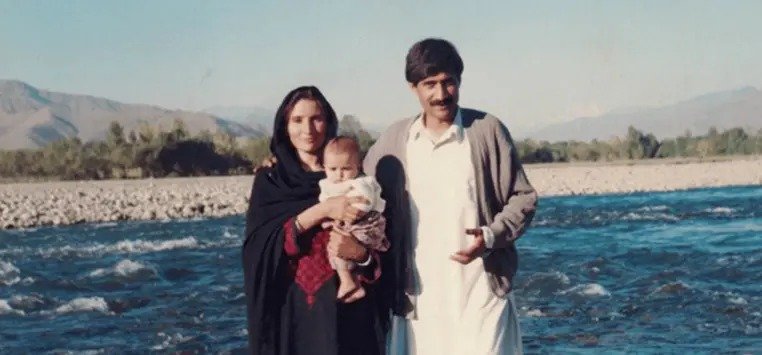

Pictured: Malala Yousafzai’s parents, Toor Pekai Yousafzai (left), and Ziauddin Yousafzai (right), and young Malala (center).

If you haven’t heard of Malala, you haven’t been paying attention. Born July 12th, 1997, Malala is the youngest Nobel Prize laureate in history, but that’s the least of her accomplishments.

First Public Entries

Malala’s first public speech took place at a press club in Peshawar, September 2008. There, she spoke out against the Taliban’s attempts to take women’s rights to education. This speech, covered by newspapers and regional television, introduced young Malala to the public eye; and in 2009, she became a peer educator at the Institute of War and Peace Reporting’s Open Minds Pakistan youth program, where she worked in regional schools to engage students on social and political issues.

After Malala’s impassioned public speech on education rights in 2008, Malala’s father Ziauddin Yousafzai approached BBC Urdu, a branch of the British Broadcasting Corporation’s global outreach, to suggest his seventh-grade daughter for a dangerous journalism project. This project intended to use an anonymous schoolgirl’s experience with life under the Taliban’s growing influence in Swat, which, at the time, had overrun Swat Valley and banned television, music, women’s education, and women in shopping centers. Additionally, the Taliban hung the bodies of policemen in town squares, and had destroyed over 100 girls’ schools.

The diary, which you can investigate here, was published under the pseudonym name “Gul Makai”, and its first entry was published publicly on the 3rd of January 2009, written by Malala’s hand and mailed to a BBC Urdu reporter.

The first heartbreaking entry recorded Malala’s thoughts during the First Battle of Swat and the shutdown of public schools: “My mother made me breakfast and I went off to school. I was afraid going to school because the Taliban had issued an edict banning all girls from attending schools. Only 11 out of 27 pupils attended the class because the number decreased because of the Pakistani Taliban's edict. My three friends have shifted to Peshawar, Lahore and Rawalpindi with their families after this edict.”

This journalism continued until the 12 of March, 2009. After the end of this BBC diary, Malala and her father were approached by the New York Times with the offer of a filmed documentary. During this time, the Second Battle of Swat displaced Malala and her family, and she and her father were separated. However, the documentary He Named Me Malala was filmed and aired internationally.

He Named Me Malala is available on most major streaming platforms.

In July of 2009, the Pakistani military had reclaimed Swat Valley, and Malala was reunited with her family.

Gaining Notice

Following He Named Me Malala, Malala has been interviewed and has appeared on television to publicly advocate for women’s education, and from 2009 to 2010 was the chair of the District Child Assembly of the Khpal Kor Foundation, a non-governmental partner of UNICEF. In 2011, she trained with Aware Girls, which peacefully opposes radicalization through education; later in 2011, she was nominated for the International Children’s Peace Prize of the Dutch KidsRights Foundation. Two months later, Malala was awarded Pakistan’s first National Youth Peace Prize by Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gillani; Gillani later opened an IT campus in the Swat Degree College for Women at Malala’s request.

In 2012, Malala began organization of the Malala Education Foundation, which aimed to support girls education, and she attended the International Marxist Summer School.

The Murder Attempt

The image of a little girl teaching terrifies grown men, and of course death threats snowed down around Malala and her family as she became publicly recognizable. Death threats against her father were proclaimed over the radio, death threats against Malala and her family were published in newspapers and slipped beneath their family door, and similar threats were published on her Facebook page.

In the summer of 2012, a Taliban spokesperson claimed that Taliban leaders unanimously agreed that they were ‘forced’ to kill the 15-year-old girl.

On October 9th, 2012, a Taliban gunman fired at Malala and two other girls (Kainat Riaz and Shazia Ramzan) as they rode a public bus from an exam in Swat Valley. One bullet hit Malala, and travelled 18 inches from the side of her left eye, through her neck, and into her shoulder.

Malala was rushed to a military hospital in Peshawar, where surgeons struggled to control swelling and damage to the left side of her brain. Malala’s family was told she had a chance of survival, and she was moved to Germany for better treatment.

The Pakistani government paid for a team of doctors to travel with Malala, and on the 13th of October, she was able to move all four of her limbs, an astonishing success for the damage to her spinal cord. Malala was later moved to treatment at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in England, and on October 17th, 2012, she awoke from her coma with a chance to recover without brain damage.

Eventually in January of 2013, Malala was again placed into operation to reconstruct her skull and restore her hearing with a cochlear implant. In July of 2014, Malala reported that her facial nerves had recovered to 96%.

She had survived, and in perhaps the most ironic poetic justice, this attack on Malala turned the world toward children’s rights to education.

Presidents and Prime Ministers, UN Secretaries, American Secretaries of State, British Foreign Secretaries, First Ladies of the United States, and entertainers and journalists the world over spoke out in support of Malala and condemnation of the Taliban. On October 15th, 2012, before Malala had recovered, the UN Special Envoy for Global Education launched a petition under the slogan “I Am Malala” to demand that no child be left out of school by 2015, which was handed to the President in Islamabad in November of the same year.

Malala published her autobiographical book by the same name, I Am Malala, in October of 2013. Naturally, this book has been banned in many areas of Pakistan and schools in the United States.

I Am Malala is available online and in most bookstores.

Obviously, only men of great honor attack teenage girls at long distance.

Her Activism Today

Malala continues her activism today, fighting for women’s and children’s rights. She has opened a school in Lebanon for Syrian refugees, funded by the Malala Fund. She has addressed the United Nations, spoken at universities, and has had audience with world powers like the Queen of England the President of the United States. She intends to return to Pakistan to run for Prime Minister.

This is in no way all of Malala’s story, and I highly encourage my readers to read about the Malala Fund, check out her numerous biographies, and watch her documentary He Named Me Malala.

Men Have A Place Here

One of Malala’s greatest sources of inspiration has been her father, Ziauddin Yousafzai. Ziauddin Yousafzai is a poet and educational activist himself, and at one time ran a chain of private schools, ther Kushal Public School. Ziauddin educated Malala himself, and enjoyed in their younger years sitting up late with Malala to discuss education and politics.

In November of 2018, Ziauddin co-published Let Her Fly, his biographical account of raising a daughter in challenge to gender discrimination and patriarchy in a small village in the Shangla district.

In his memoir, Ziauddin writes about his daughter’s powerful voice: “When I say of Malala ‘I did not clip her wings,’ what I mean is that when she was small, I broke the scissors used by the society to clip girls’ wings.”

“I did not let those scissors near Malala. I wanted to let her fly high in the sky, not scratch around in a dusty courtyard, grounded by social norms.”

Read more about Let Her Fly here.

Ziauddin also writes about his wife, which in itself is a break in tradition, as many in conservative Pashtun society do not mention the names of female relatives. In this memoir, he calls his wife Tor Pekai his best friend.

Tor Pekai has said in interview that “I found Ziauddin a different man who gave me the courage to speak in front of our male family members”.

In Conclusion

Men, where is your place in the liberated world? It’s here, in the fatherhood and brotherhood of the voices of women; here, where you can join women in protecting one another from the ‘scissors used by the society to clip girls’ wings’.

Speaking of her Let Her Fly,

why did her parents name her Malala?

Malala is named after the Afghan folk heroine Malalai of Maiwand, who rallied Afghan fighters during the Second Anglo-Afghan War with the chilling cry, “Young love! If you do not fall in the battle of Maiwand, by God, someone is saving you as a symbol of shame!”

If you don’t understand why a woman would cry this to her soldiers,

think about it twice.

Get Involved

Malala is still out here, fighting for the rights of women and children. If you want to help fund her organization to keep girls learning, you can donate here.

The Malala Fund is currently aiding girls’ education in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Lebanon, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tanzania, and Turkey.

Thanks for Reading

Remember:

An ideology only panics when it knows it’s dying.

Want to stay on top of the newest information? Sign up for the OCC newsletter and be the first in the know!

Follow Alice on social media so you never miss an event or an update - or, join the Red Veil Lounge to chat directly or join an event!